Pronghorn request research group access

Pronghorn request research group access

Assignments

Please finish below assignment before due date

- DataCamp Introduction to Shell Due by 9/14/20

- DataCamp Downloading Data on the Command Line Due by 9/14/20

- Edit files on command line Due by 9/21/20

Command Line Bootcamp

A tutorial that teaches you how to work at the command-line. You’ll learn all the basic skills needed to start being productive in the UNIX terminal.

Explainshell

Connect to Pronghorn

ssh <YOURID>@pronghorn.rc.unr.edu

Your first Unix command.

echo "Hello World!"

Basic commands

| Category | comnmand |

|---|---|

| Navigation | cd, ls, pwd |

| File creation | touch,nano,mkdir,cp,mv,rm,rmdir |

| Reading | more,less,head,tail,cat |

| Compression | zip,gzip,bzip2,tar,compress |

| Uncompression | unzip,gunzip,bunzip2,uncompress |

| Permissions | chmod |

| Help | man |

pwd

Returns you the

presentworkingdirectory (print working directory)$ pwd/home/usernameThis means, you are now working in the home directory, which is located under your ID. The directory that will be the first directory when you log-in. You can also avoid writing the full path by using

~in front of your username or simply.~

mkdir

To create a directory, mkdir

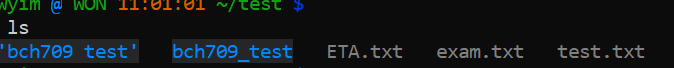

make directorycan be used. $ mkdir$ mkdir bch709_testUnlike PC/Mac folders, here you can have space in different way (some special characters are okay). You can also specify the path where you want to create your new folder.

$ mkdir bch709\ testLike most Unix commands, mkdir supports command-line options which let you alter its behavior and functionality. Command-like options are – as the name suggests – optional arguments that are placed after the command name. They often take the form of single letters (following a dash). If we had used the -p option of the mkdir command we could have done this in one step.

$ mkdir -p bch709_test/help

cd

This is

changesdirectory. $ cd$ cd bch709_test$ pwd/home/username/bch709_testChanges your present location to the parent directory

$ cd ..Please check your current location with

pwd.Changes your present location to the Grand parent (two levels upward) directory.

$ cd ../../Please check your current location with

pwd. If this is confusing, please use our command line server to understand the location and folders. Go to the root directory$ cd /Go to your home directory

$ cd ~Go to specific directory

$ cd ~/bch709_test/helpGo to upward directory $ cd ../

Absolute and relative paths

cd.. allows us to change directory relative to where we are now. You can also always change to a directory based on its absolute location. E.g. if you are working in the~/bch709_testdirectory and you want to change to the~/bch709_test/helpdirectory, then you could do either of the following: absolute path$ cd /home/<userid>/bch709_test/helprelative path

$ cd ../

The way back home

Again, your home directory is

/home/<userid>/. . they take you back to your home directory (from wherever you were). You will frequently want to jump straight back to your home directory, and typing cd is a very quick way to get there.cd ~cdcd ~/

Pressing < TAB > key

You can type in first few letters of the directory name and then press tab to auto complete rest of the name (especially useful when the file/directory name is long). If there is more than one matching files/directories, pressing tab twice will list all the matching names. Saving keystrokes may not seem important now, but the longer that you spend typing in a terminal window, the happier you will be if you can reduce the time you spend at the keyboard. Especially as prolonged typing is not good for your body. So the best Unix tip to learn early on is that you can [tab complete][] the names of files and programs on mostUnix systems. Type enough letters to uniquely identify the name of a file, directory, or program and press tab – Unix will do the rest. E.g. if you type ‘tou’ and then press tab, Unix should autocomplete the word to ‘touch’ (this is a command which we will learn more about in a minute). In this case, tab completion will occur because there are no other Unix commands that start with ‘tou’. If pressing tab doesn’t do anything, then you have not havetyped enough unique characters. In this case pressing tab twice will show you all possible completions. This trick can save you a LOT of typing!

Pressing <Arrow up/down> key

You can also recall your previous commands by pressing up/down arrow or browse all your previously used commands by typing history on your terminal.

Copy & Paste

If you drag it will copy the text in terminal. If you use right click, then it will paste. In macOS, it depends on setting. You can still use command + c and command + v.

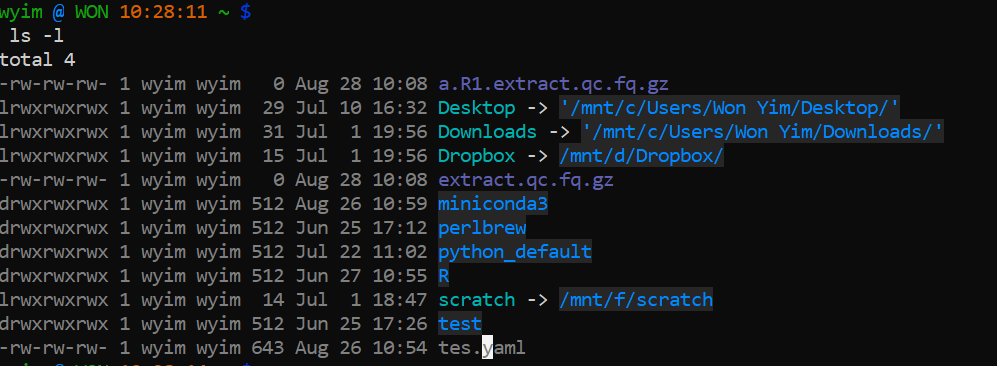

ls

The contents of a directory can be viewed using ls (list) command.

Like any other command, you can use absolute path or abbreviated path. There are also various options available for ls command. Some very useful options include: Lists files in lengthy or detailed view

$ ls –lLists files, sorted based on creation time

$ ls –tLists files, sorted based on size

$ ls –SLists all the files, do not ignore entries starting with .

$ ls -aFor each file or directory we now see more information (including file ownership and modification times). The ‘d’ at the start of each line indicates that these are directories. There are many, many different options for the ls command. Try out the following (against any directory of your choice) to see how the output changes

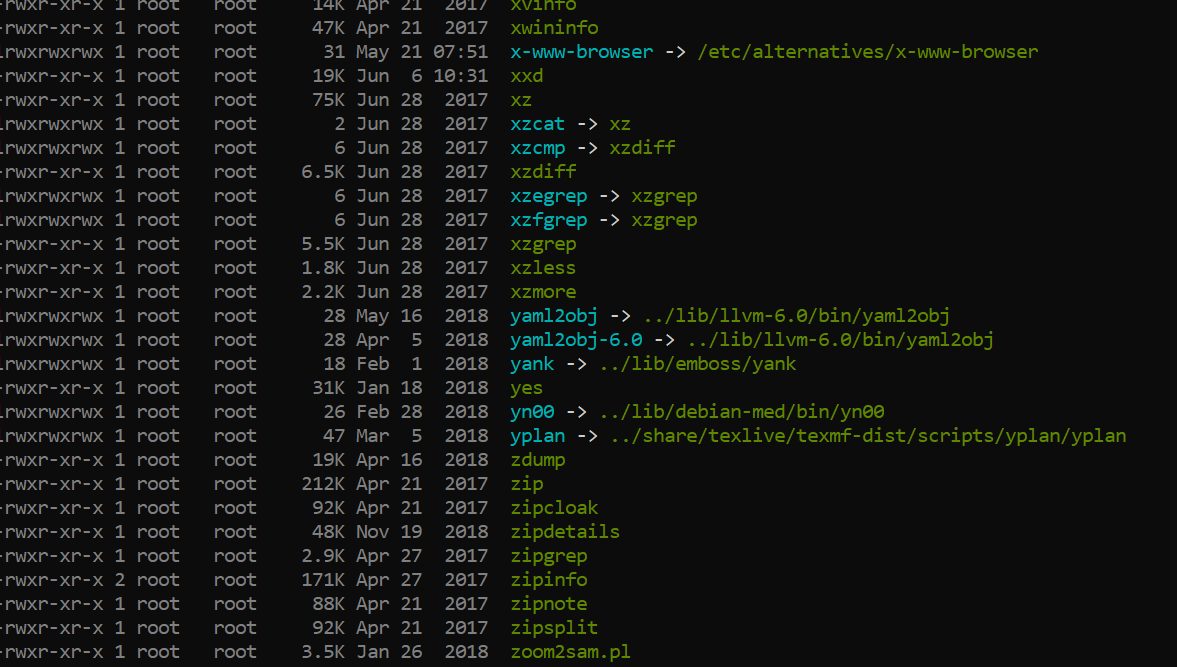

$ ls -l $ ls -R $ ls -l -t -r $ ls -ltr $ ls -lhBecause your directory is almost empty. They will not show anything a lot. Let’s check other folder. Somthing like below.

$ ls -l /usr/bin/

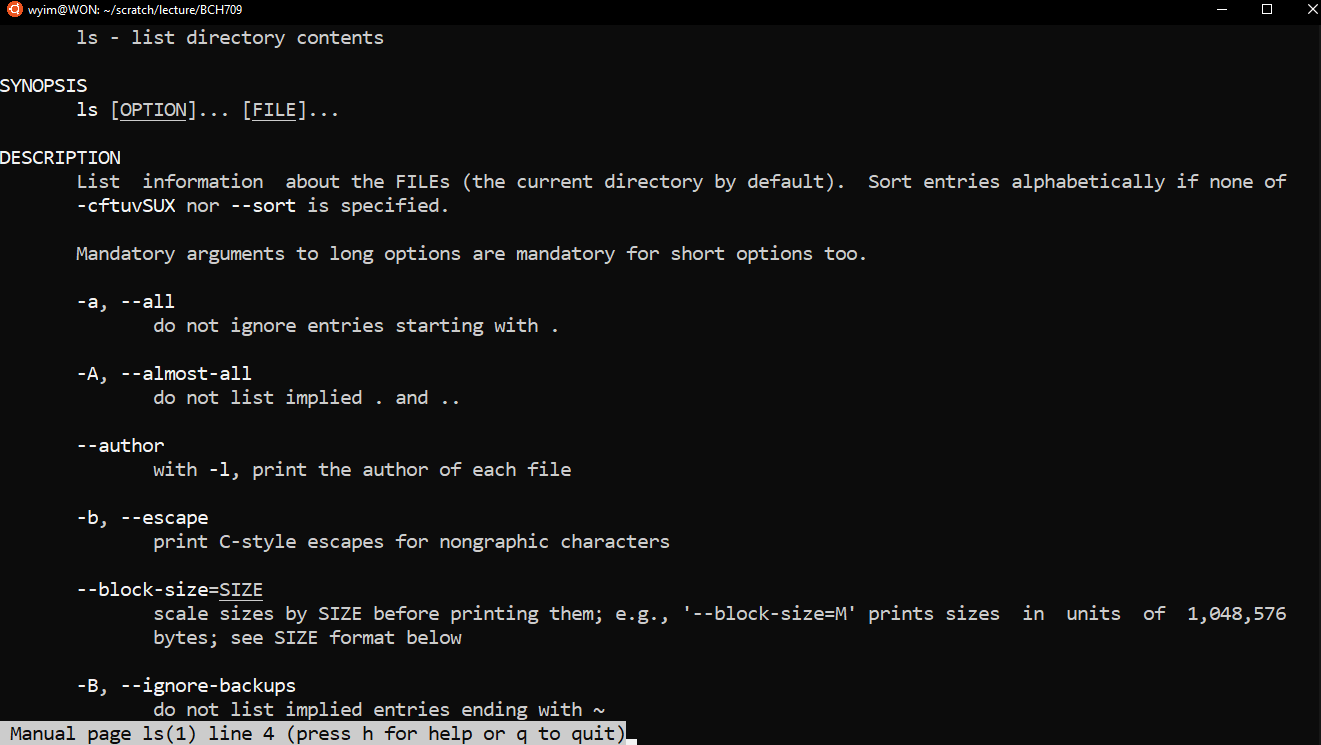

man & help

If every Unix command has so many options, you might be wondering how you find out what they are and what they do. Well, thankfully every Unix command has an associated ‘manual’ that you can access by using the man command. E.g.

$ man ls $ man cd $ man manor

you can call help directrly from command.

$ ls --help $ cd --help

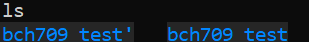

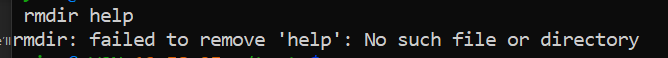

rmdir

To remove a directory, rmdir

remove directorycan be used. $ rmdir$ cd ~/ $ ls

$ rmdir help

$ ls bch709_test $ rmdir bch709_test/help $ ls bch709_testYou have to be outside a directory before you can remove it with rmdir

touch

The following sections will deal with Unix commands that help us to work with files, i.e. copy files to/from places, move files, rename files, remove files, and most importantly, look at files. First, we need to have some files to play with. The Unix command touch will let us create a new, empty file.

$ touch --help $ touch test.txt $ touch exam.txt $ touch ETA.txt $ ls

$ ls -a

mv

We want to move these files to a new directory (‘temp’). We will do this using the Unix

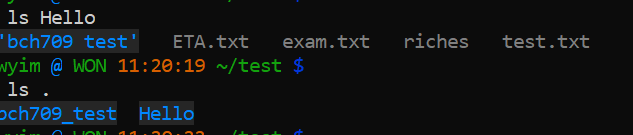

mv(move) command. Remember to use tab completion:$ mkdir Hello $ mv test.txt Hello $ mv exam.txt Hello $ mv ETA.txt Hello $ ls HelloFor the mv command, we always have to specify a source file (or directory) that we want to move, and then specify a target location. If we had wanted to, we could have moved both files in one go by typing any of the following commands:

$ mv *.txt Hello $ mv *t Hello $ mv *e* HelloThe asterisk * acts as a wild-card character, essentially meaning ‘match anything’. The second example works because there are no other files or directories in the directory that end with the letter ‘t’ (if there were, then they would be moved too). So all the ‘bch709 test’, bch709_test will be move. Likewise, the third example works because only those two files contain the letters ‘e’ in their names and ‘bch709 test’, bch709_test and Hello folder has e so it will move everything except for ETA.txt and will give you error

cannot move 'Hello' to a subdirectory of itself. Using wild-card characters can save you a lot of typing but need to be careful The ? character is also a wild-card but with a slightly different meaning. See if you can work out what it does.

Renaming files by mv

In the earlier example, the destination for the mv command was a directory name (Hello). So we moved a file from its source location to a target location, but note that the target could have also been a (different) file name, rather than a directory. E.g. let’s make a new file and move it whilst renaming it at the same time

$ touch rags $ ls $ mv rags Hello/riches $ ls Hello/

Of course you can do without moving

In this example we create a new file (‘rags’) and move it to a new location and in the process change the name (to ‘riches’). So mv can rename a file as well as move it. The logical extension of this is using

mvto rename a file without moving it. You may also have access to a tool calledrename, type man rename for more information.$ mv Hello/riches Hello/rags

Moving directory by mv

It is important to understand that as long as you have specified a ‘source’ and a ‘target’ location when you are moving a file, then it doesn’t matter what your current directory is. You can move or copy things within the same directory or between different directories regardless of whether you are in any of those directories. Moving directories is just like moving files:

$ mv Hello/bch709_test .

.means current directory$ ls Hello $ ls .

rm

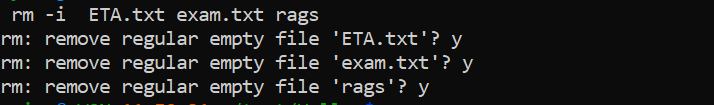

Removing fileYou’ve seen how to remove a directory with the rmdir command, but rmdir won’t remove directories if they contain any files. So how can we remove the files we have created (inside temp)? In order to do this, we will have to use the rm (remove) command. Please read the next section VERY carefully. Misuse of the rm command can lead to needless death & destruction. Potentially, rm is a very >dangerous command; if you delete something with rm, you will not get it back! It is possible to delete everything in your home directory (all directories and subdirectories) with rm.

That is why it is such a dangerous command. Let me repeat that last part again. It is possible to delete EVERY file you have ever created with the rm command. Luckily there is a way of making rm a little bit safer. We can use it with the -i (interactive) command-line option which will ask for confirmation before deleting anything (remember to use tab-completion):

$ cd Hello $ ls $ rm -i ETA.txt exam.txt ragswill ask permission for each step:

ls

cp

Copying files with the cp (copy) command has a similar syntax as mv, but the file will remain at the source and be copied to the target location. Remember to always specify a source and a target location. Let’s create a new file and make a copy of it:

$ touch file1 $ cp file1 file2 $ lsWhat if we wanted to copy files from a different directory to our current directory? Let’s put a file in our home directory (specified by ~, remember) and copy it to the lecture directory.

$ touch ~/file3 $ cp ~/file3 ~/HelloThe cp command also allows us (with the use of a command-line option) to copy entire directories. Use man cp to see how the -R or -r options let you copy a directory recursively. Please check help

cp --help

using . < Dot> ?

In Unix, the current directory can be represented by a . (dot) character. You will often use for copying files to the directory that you are in. Compare the following:

ls ls . ls ./In this case, using the dot is somewhat pointless because ls will already list the contents of the current directory by default. Also note how the trailing slash is optional.

Clean up and start new

Before we start other session, let’s clean up folders

$ cd ~/ $ lsPlease do it first and check the solution below.

Clean the folder with contents

How can we clean up

bch709_testHello?rm -R <folder name>

Downloading file

Let’s downloading one file from website. There are several command to download file. Such as ‘wget’,’curl’,’rsync’ etcs. but this time we will use

curl. File locationhttps://raw.githubusercontent.com/plantgenomicslab/BCH709/gh-pages/bch709_student.txtHow to use curl?

How to download from web file?

curl -L -o <output_name> <link>curl -L -o bch709_student.txt https://raw.githubusercontent.com/plantgenomicslab/BCH709/gh-pages/bch709_student.txt

Viewing file contents

There are various commands to print the contents of the file in bash. Most of these commands are often used in specific contexts. All these commands when executed with filenames displays the contents on the screen. Most common ones are less, more, cat, head and tail.

lessFILENAME try this:less bch709_student.txtDisplays file contents on the screen with line scrolling (to scroll you can use arrow keys, PgUp/PgDn keys, space bar or Enter key). When you are done press q to exit.

moreFILENAME try this:more bch709_student.txtLike less command, also, displays file contents on the screen with line scrolling but uses only space bar or Enter key to scroll. When you are done press q to exit.

catFILENAME try this:cat bch709_student.txtSimplest form of displaying contents. It catalogs the entire contents of the file on the screen. In case of large files, entire file will scroll on the screen without pausing

headFILENAME try this:head bch709_student.txtDisplays only the starting lines of a file. The default is first ten lines. But, any number of lines can be displayed using –n option (followed by required number of lines).

tailFILENAME try this:tail bch709_student.txtSimilarto head, but displays the last 10 lines. Again –n option can be used to change this. More information about any of these commands can be found in man pages (man command)

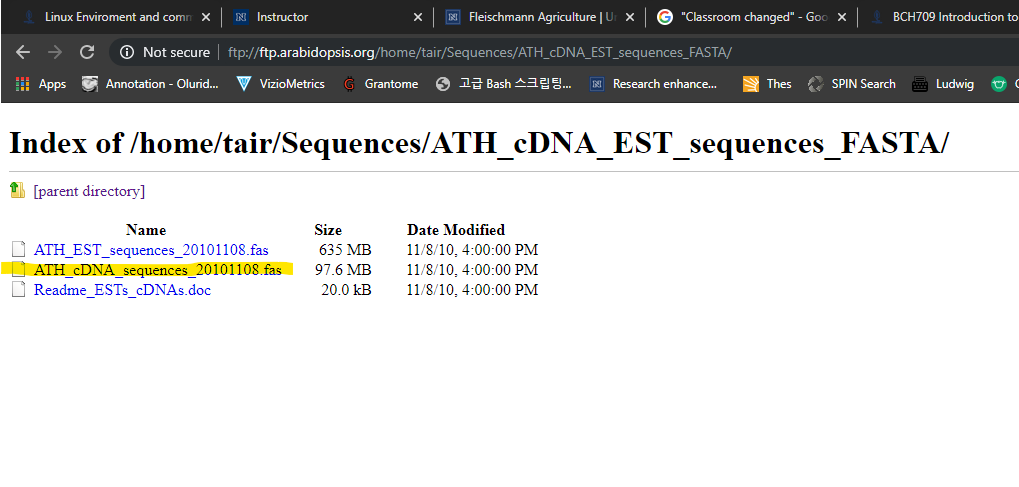

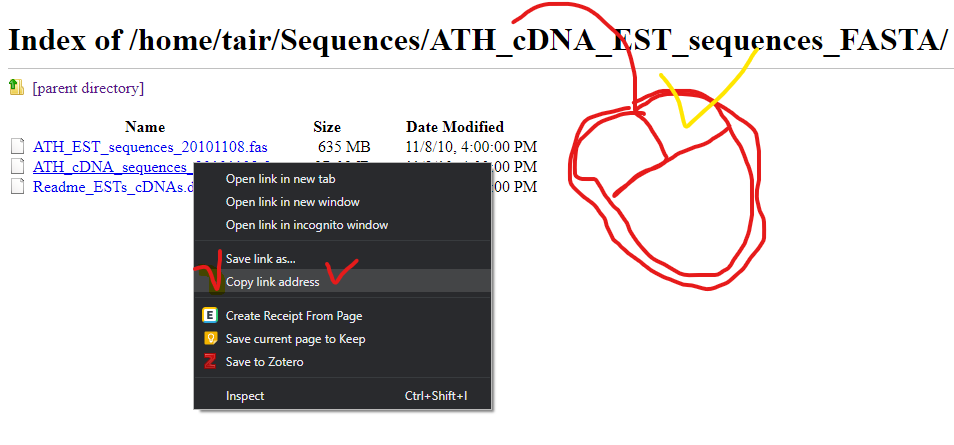

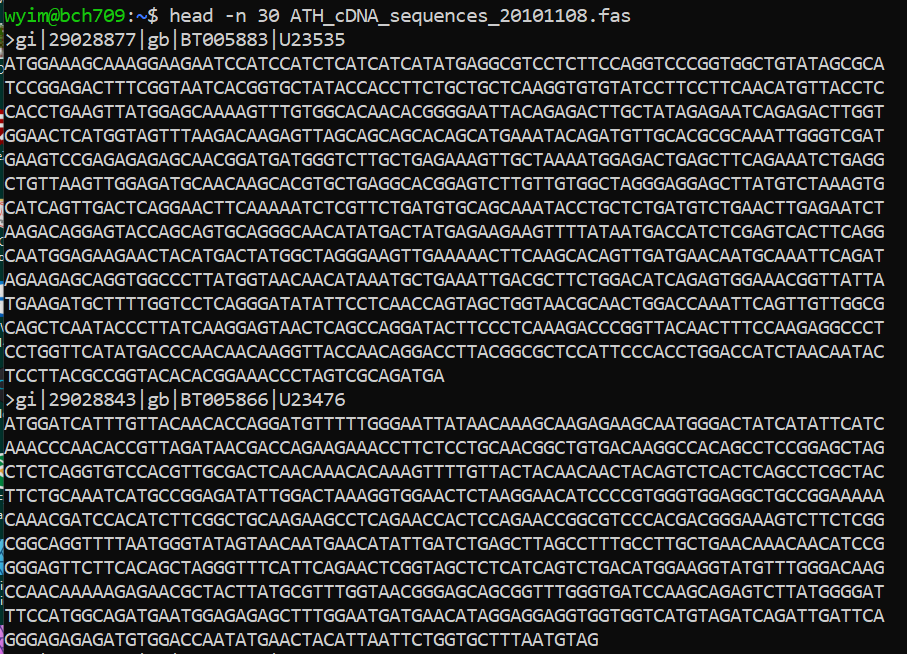

Let’s Download bigger data

Please go to below wesite.

ftp://ftp.arabidopsis.org/home/tair/Sequences/ATH_cDNA_EST_sequences_FASTA/Please download yellow marked file.

How to download

curl -L -O ftp://ftp.arabidopsis.org/home/tair/Sequences/ATH_cDNA_EST_sequences_FASTA/ATH_cDNA_sequences_20101108.fas

Viewing file contents

What is the difference in

less,tail,moreandhead?

What are flags (parameters / options)?

A “flag” in Unix terminology is a parameter added to the command. See for example

$ lsversus

$ ls -lTypically flags make programs behave differently or report their information in different ways.

How to find out what flags are available?

You can use the manual to learn more about a command:

$ man lswill produce

What if the tools does not have manual page?

Only tools that come with Unix will have a manual. For other software the -h, -help or –help command will typically print instructions for their use.

$ curl --helpIf the help flag is not recognized you will need to find the manual for the software.

What are flag formats?

Traditionally Unix tools use two flag forms:

short form: single minus - then one letter, like -o, ’-L‘

long form: double minus – then a word, like –output, –Location In each case the parameter may stand alone as a toggle (on/off) or may take additional values after the flag. -o

or -L Now some bioinformatics tools do not follow this tradition and use a single - character for both short and long options. -g and -genome. **Using flags is a essential to using Unix. Bioinformatics tools typically take a large number of parameters specified *via* flags**. The correctness of the results critically depends on the proper use of these parameters and flags.

How many lines does the file have?

You can pipe the output of you stream into another program rather than the screen. Use the | (Vertical Bar) character to connect the programs. For example, the wc program is the word counter.

cat bch709_student.txt | wcprints the number of lines, words, and characters in the stream:

12 33 193How many lines?

cat bch709_student.txt | wc -l12of course we can use

wcdirectlywc -l bch709_student.txtThat is equivalent to:

cat bch709_student.txt | wc -lIn general, it is a better option to open a stream with cat then pipe the flow into the next program. Later you will see that it is easier to design, build and understand more complex pipelines when the data stream is opened at the beginning as a separate step.

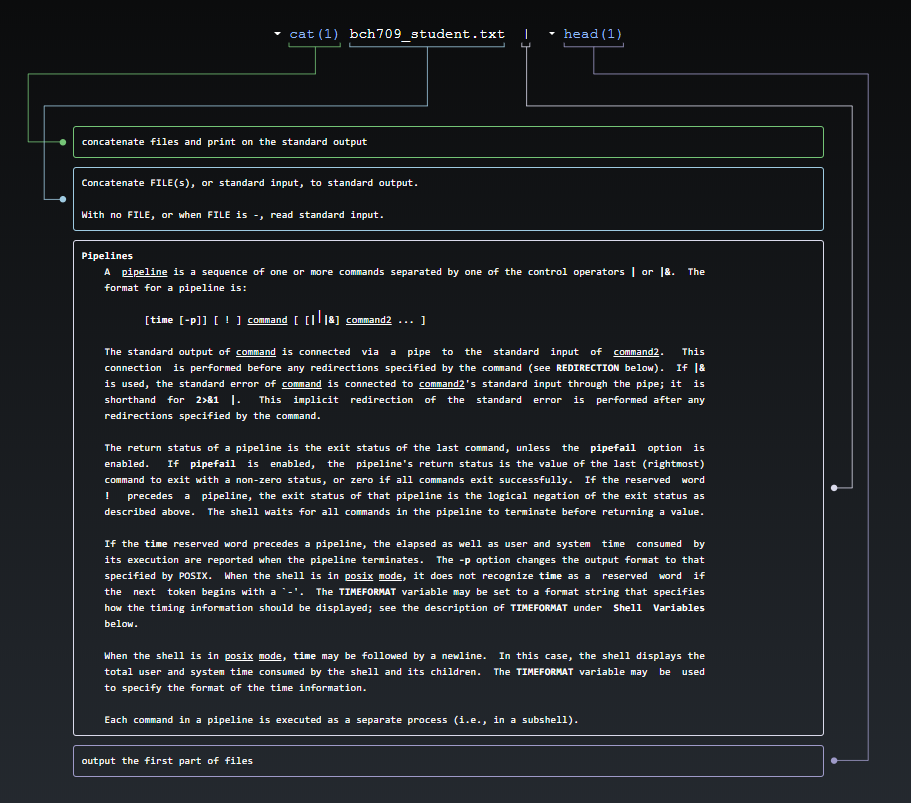

Again, let’s do head.

cat bch709_student.txt | head

is this equivalent to?

head bch709_student.txt

grep

Globally search a Regular Expression and Print is one of the most useful commands in UNIX and it is commonly used to filter a file/input, line by line, against a pattern eg., to print each line of a file which contains a match for pattern. Please check option with :

grep --helpWith options, syntax is

grep [OPTIONS] PATTERN FILENAMELet’s find how many people use macOS? First we need to check file.

$ wc -l bch709_student.txt$ less bch709_student.txtHow can we find the macOS people? Now we can use

grep$ cat bch709_student.txt | grep MacOSHow can we count?

$ cat bch709_student.txt | grep MacOS | wc -lHow about this?

$ grep MacOS bch709_student.txt | wc -lHow about this?

$ grep -c MacOS bch709_student.txtWith other options (flags)

$ grep -v Windows bch709_student.txtWith multiple options (flags)

$ grep -c -v Windows bch709_student.txt$ grep --color -i macos bch709_student.txt

How do I store the results in a new file?

The > character is the redirection.

$ grep -i macos bch709_student.txt > mac_student$ cat bch709_student.txt | grep -i windows > windows_studentPlease check with

catorless

Do you want to check difference?

$ diff mac_student windows_student$ diff -y mac_student windows_student

How can I select name only? (cut)

$ cat bch709_student.txt | cut -f 1$ cut -f 1 bch709_student.txt

How can I sort it ? (sort)

cut -f 1 bch709_student.txt | sort$ sort bch709_student.txt $ sort -k 2 bch709_student.txt $ sort -k 1 bch709_student.txt$ sort -k 1 bch709_student.txt | cut -f 1Save?

sort -k 1 bch709_student.txt | cut -f 1 > name_sort

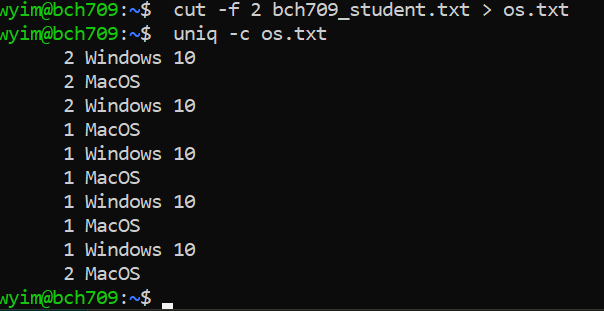

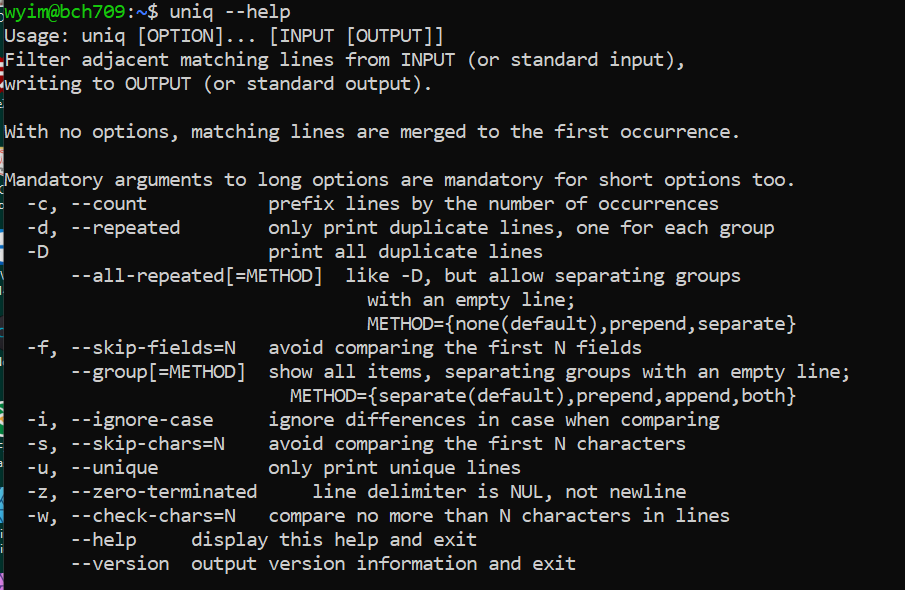

uniq

uniq command removes duplicate lines from a sorted file, retaining only one instance of the running matching lines. Optionally, it can show only lines that appear exactly once, or lines that appear more than once. uniq requires sorted input since it compares only consecutive lines.

$ cut -f 2 bch709_student.txt > os.txt$ uniq -c os.txt

$ sort os.txt | uniq -c

Of course you can use

sortindependently.$ sort os.txt > os_sort.txt $ uniq -c os_sort.txt$ uniq --help

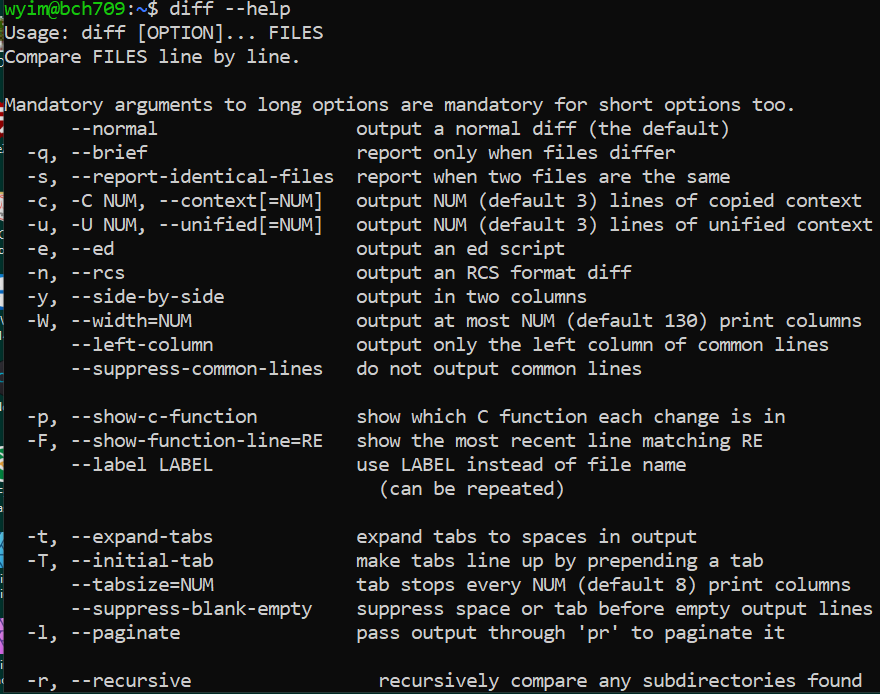

diff

diff (difference) reports differences between files. A simple example for diff usage would be ` $ diff FILEA FILEB ` When you try to use new command, please check with

--help.$ diff os.txt os_sort.txt$ diff -y os.txt os_sort.txt$ sort os.txt | diff -y - os_sort.txt

There are still a lot of command that you can use. Such as paste, comm, join, split etc.

Oneliners

Oneliner, textual input to the command-line of an operating system shell that performs some function in just one line of input. This need to be done with “|”. For advanced usage, please check this

FASTA format

The original FASTA/Pearson format is described in the documentation for the FASTA suite of programs. It can be downloaded with any free distribution of FASTA (see fasta20.doc, fastaVN.doc or fastaVN.me—where VN is the Version Number).

The first line in a FASTA file started either with a “>” (greater-than; Right angle braket) symbol or, less frequently, a “;” (semicolon) was taken as a comment. Subsequent lines starting with a semicolon would be ignored by software. Since the only comment used was the first, it quickly became used to hold a summary description of the sequence, often starting with a unique library accession number, and with time it has become commonplace to always use “>” for the first line and to not use “;” comments (which would otherwise be ignored).

Following the initial line (used for a unique description of the sequence) is the actual sequence itself in standard one-letter character string. Anything other than a valid character would be ignored (including spaces, tabulators, asterisks, etc…). Originally it was also common to end the sequence with an “*” (asterisk) character (in analogy with use in PIR formatted sequences) and, for the same reason, to leave a blank line between the description and the sequence.

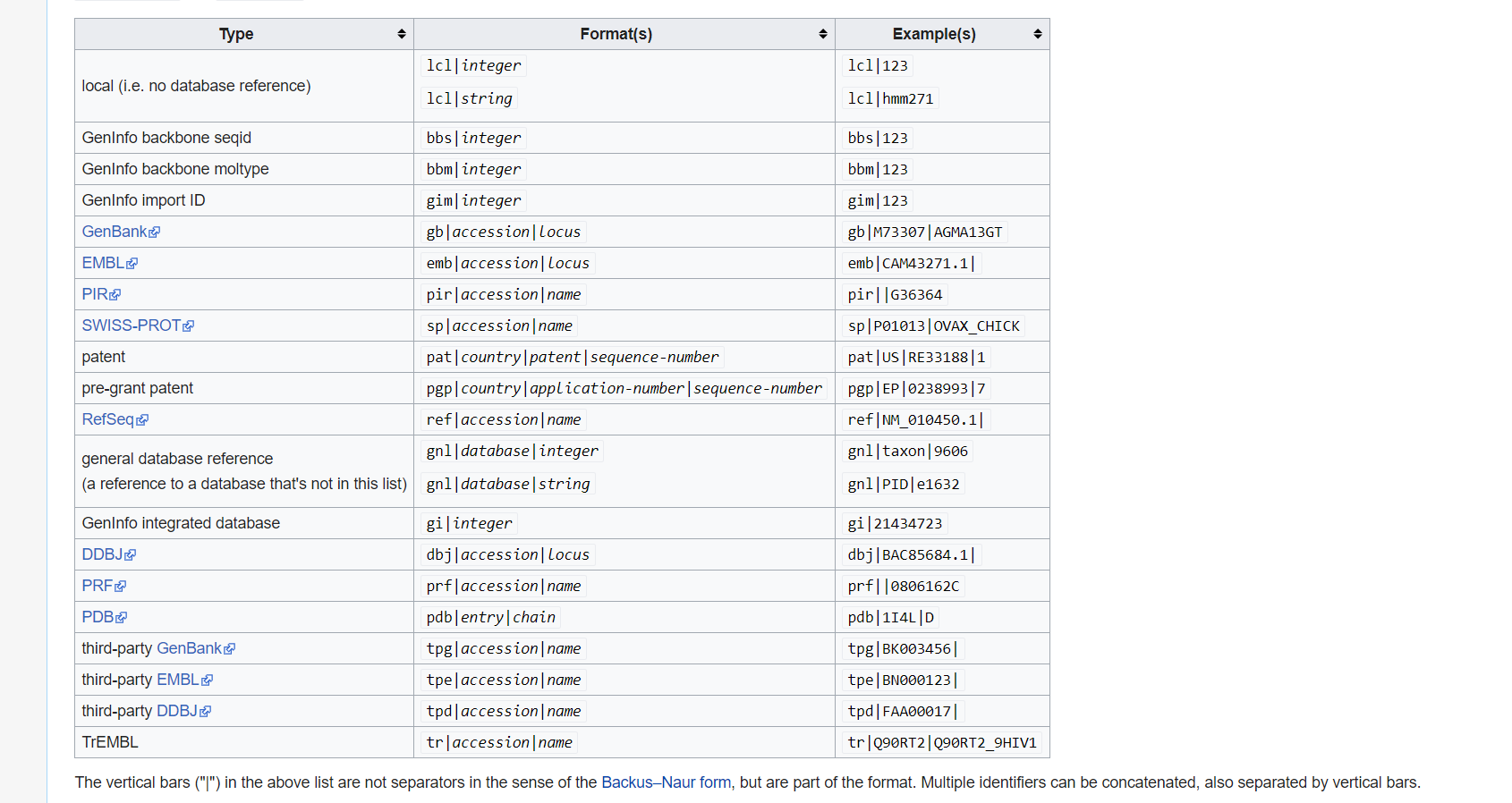

Description line

The description line (defline) or header/identifier line, which begins with ‘>’, gives a name and/or a unique identifier for the sequence, and may also contain additional information. In a deprecated practice, the header line sometimes contained more than one header, separated by a ^A (Control-A) character. In the original Pearson FASTA format, one or more comments, distinguished by a semi-colon at the beginning of the line, may occur after the header. Some databases and bioinformatics applications do not recognize these comments and follow the NCBI FASTA specification.

FASTA file handling with command line.

Please check one fasta file

$ ls ATH_cDNA_sequences_20101108.fas

previous example

curl -L -O ftp://ftp.arabidopsis.org/home/tair/Sequences/ATH_cDNA_EST_sequences_FASTA/ATH_cDNA_sequences_20101108.fas

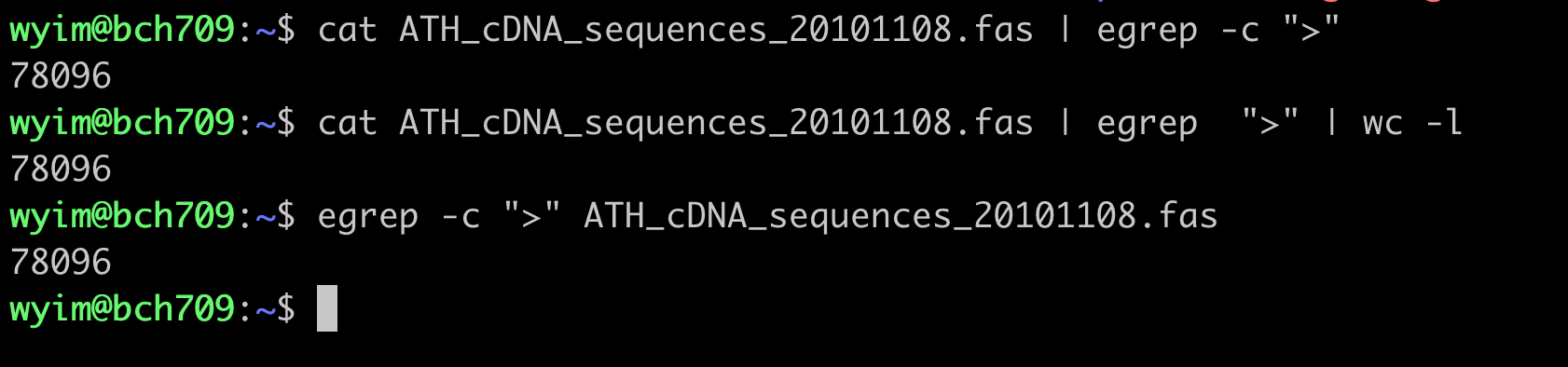

count cDNA

How many cDNA in this fasta file?

Please use grep wc to find number.

fasta count

count DNA letter

How many sequences (DNA letter) in this fasta file? Please use

grepwcto find number.

what is GI and GB?

Collect GI

How can I collect GI from FASTA description line?

Please use grep cut to find number.

Sequence redundancy

Does GI have any redundancy? Please use

grepwcdiffto solve.

GFF file

The GFF (General Feature Format) format consists of one line per feature, each containing 9 columns of data, plus optional track definition lines. The following documentation is based on the Version 3 (http://gmod.org/wiki/GFF3) specifications.

Please download below file

http://www.informatics.jax.org/downloads/mgigff3/MGI.gff3.gz

What is .gz ?

file MGI.gff3.gz

Compression

There are several options for archiving and compressing groups of files or directories. Compressed files are not only easier to handle (copy/move) but also occupy less size on the disk (less than 1/3 of the original size). In Linux systems you can use zip, tar or gz for archiving and compressing files/directories.

ZIP compression/extraction

zip OUTFILE.zip INFILE.txt Compress INFILE.txt zip -r OUTDIR.zip ## DIRECTORY Compress all files in a DIRECTORY into one archive file (OUTDIR.zip) zip -r OUTFILE.zip . -i *.txt ## Compress all txt files in a DIRECTORY into one archive file (OUTFILE.zip) unzip SOMEFILE.zip

TAR compression/extraction

tar (tape archive) utility saves many files together into a single archive file, and restores individual files from the archive. It also includes automatic archive compression/decompression options and special features for incremental and full backups.

tar -cvf OUTFILE.tar INFILE # archive INFILE tar -czvf OUTFILE.tar.gz INFILE # archive and compress file INFILE tar -tvf SOMEFILE.tar #list contents of archive SOMEFILE.tar tar -xvf SOMEFILE.tar # extract contents of SOMEFILE.tar tar -xzvf SOMEFILE.tar.gz #extract contents of gzipped archive SOMEFILE.tar.gz tar -czvf OUTFILE.tar.gz DIRECTORY #archive and compress all files in a directory into one archive file tar -czvf OUTFILE.tar.gz \*.txt #archive and compress all ".txt" files in current directory into one archive file tar -czvf backup.tar.gz BACKUP_WORKSHOP

Gzip compression/extraction

gzip (gnu zip) compression utility designed as a replacement for compress, with much better compression >and no patented algorithms. The standard compression system for all GNU software. gzip SOMEFILE compress SOMEFILE (also removes uncompressed file) gunzip SOMEFILE.gz uncompress SOMEFILE.gz (also removes compressed file)

gzip the file MGI.gff3.gz and examine the size. gunzip it back so that you can use this file for thelater exercises.

$ gunzip MGI.gff3.gz $ ls –lh $ gzip MGI.gff3 $ ls -lh $ gunzip MGI.gff3.gz

GFF3 Annotations

Print all sequences annotated in a GFF3 file.

cut -s -f 1,9 MGI.gff3 | grep $'\t' | cut -f 1 | sort | uniq

Determine all feature types annotated in a GFF3 file.

grep -v '^#' MGI.gff3 | cut -s -f 3 | sort | uniq

Determine the number of genes annotated in a GFF3 file.

grep -c $'\tgene\t' MGI.gff3

Extract all gene IDs from a GFF3 file.

grep $'\tgene\t' MGI.gff3 | perl -ne '/ID=([^;]+)/ and printf("%s\n", $1)'

Print all CDS.

cat MGI.gff3 | cut -f 3 | grep CDS |

Print CDS and ID

cat MGI.gff3 | cut -f 1,3,4,5,7,9 | head

cat MGI.gff3 | cut -f 1,3,4,5,7,9 | grep CDS | head

cat MGI.gff3 | cut -f 1,3,4,5,7,9 | grep CDS | sed 's/;.*//g' | head

cat MGI.gff3 | cut -f 1,3,4,5,7,9 | grep CDS | sed 's/;.*//g' | sed 's/ID=//g' | head

cat MGI.gff3 | cut -f 1,3,4,5,7,9 | grep $'\tCDS\t' | sed 's/;.*//g' | sed 's/ID=//g' | head

Print length of each gene in a GFF3 file.

grep $'\tgene\t' MGI.gff3 | cut -s -f 4,5 | perl -ne '@v = split(/\t/); printf("%d\n", $v[1] - $v[0] + 1)'

Extract all gene IDs from a GFF3 file.

grep $'\tgene\t' MGI.gff3 | perl -ne '/ID=([^;]+)/ and printf("%s\n", $1)'

Time and again we are surprised by just how many applications it has, and how frequently problems can be solved by sorting, collapsing identical values, then resorting by the collapsed counts. The skill of using Unix is not just that of understanding the commands themselves. It is more about recognizing when a pattern, such as the one that we show above, is the solution to the problem that you wish to solve. The easiest way to learn to apply these patterns is by looking at how others solve problems, then adapting it to your needs.